BOOK EXCERPTS

At the FRONT

The book is based on in-depth interviews with my father (1921 - 2015) about his war experience as infantryman at the front in Russia and Normandy in WWII. He was twenty years old when he was shipped to the Russian front the first time. He was a conscript.

Parallel to the conversations with my father I also studied the documents of the relevant divisions in the Federal Archives in Freiburg to place the individual experiences in a larger military context.

How the Book Starts ...

By Train from Cologne to the Front in Russia

Cologne, March 1942

The barracks had disgorged their newly trained soldiers just in time for spring. They gathered like migratory birds on the platforms of Cologne's Central Station. The faces were fresh and healthy and the hair was cut according to the fashion of the time: neck short and top hair longer. They stood together in small groups and some of them already knew each other from basic training. No one knew on which front he would be deployed since each location was confidential.

The military situation in which Germany found itself at the time made guesswork all the more difficult. All neighbouring states except Switzerland had come under the control of Germany;

1938 - Austria and German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia (Sudetenland) were annexed by Germany.

1939 - Occupation and division of Poland. The remainder of Czechoslovakia came under German control.

1940 - Occupation of the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Denmark. Invasion of Norway and North Africa

1941 – Invasion of Yugoslavia, Greece and the Soviet Union.

For the young German soldiers now facing active deployment for the first time, there were only two possibilities; either the men were assigned to an occupation force abroad or sent to fight on an active sector of the front. In March 1942, there were two such major sectors; North Africa and the Eastern Front. The Eastern Front began at the Barents Sea on the Arctic Ocean in northern Finland and stretched through Russia all the way down to Crimea in the Black Sea. Thus, the western member states of the Soviet Union were already in German hands; Belarus, the Baltic states and Ukraine.

Aged 20, Clemens was one of the soldiers being sent to the front for the first time. At the station, he looked for the commandant's office where he would learn the initial details of his trip. The young man presented his pay book and the officer leafed through his index cards. He looked at Clemens: "As of now you are assigned to the 95th Infantry Division."

He actually belonged to the 78th Infantry Regiment of the 26th Infantry Division, the home division of conscripts from the Rhineland and Münster region. At that moment, the 26th Infantry Division was deployed at Rshew, the most exposed sector of the front near Moscow. Therefore, it was either luck or deliberate calculation that he, as a recruit, was not sent to this most dangerous spot. Now he was to be posted to the 95th Infantry Division, but where was this unit located?!

The officer provided the necessary transport details: "You will be travelling by train number x, departing from platform y at such and such time, and you will be in freight car number z." Curiosity made Clemens ask: "Where are we going?" The honest reply was, "I don't know, but the direction is East."

Photo top: Central Station in Cologne in 1941

The map shows the train route from Cologne to Kolpna in Russia, where Clemens is posted to the front line for the first time.

Distance: 2300 km

Excerpt from Chapter 2:

Summer Offensive

What Does General Zickwolff Know about the Planned Summer Offensive?

On 16th May 1942, the new division commander Friedrich Zickwolff wrote in the division's war diary:

"We do not know whether we ... will attack. And if that happens, we do not know in which part of our section we shall attack."

Mentally, he prepared himself for a possible attack. He selected a specific sector of the front, from which the division could attack very advantageously. But how did the enemy's situation look at that point? Zickwolff dispatched reconnaissance squads at night to find out. Each piece of the puzzle would help to determine the best time and place for the attack.

In the weeks of waiting, Zickwolf had the men out to collect the weapons, ammunition and vehicles that had been abandoned on the winter battlefield. Any usable material was returned to the depots. The Germans were frugal due to scarce resources.

In early June 1942, all relevant Generals received orders to prepare for their division participating in the Summer Offensive. The 95th Infantry Division incorporated two additional battalions transferred from the Austrian army as reserve formations.

Zickwolff emphasized that all newcomers were to be well trained:

"The replacement draft for the 95th ID has so far only received basic training for a short time, usually only two months. Frequently repeated experience shows that particularly high losses result when insufficiently trained and unaccustomed replacement troops are committed to battle in larger formations. The training of such reserves therefore requires special support from experienced front-line personnel who communicate their experience ... and familiarize them with the enemy's mode of combat."

Excerpt from Chapter 3:

In the Rshew Salient

On the General Staff map of 1st November 1942, the location of the 95th Infantry Division is circled.

The Raid

The night, like the previous nights, was bitterly cold. Winter began to take hold. Snow had not yet fallen, but white frost covered the ground in the early morning. The men had already risen in the dark and had eaten their last few scraps for breakfast in the dawn light.

"We don't have that much in our stomachs," said one, "if we get a stomach wound, we won't die so quickly."

This was a frequent theme in all trenches; if you eat a lot before an assault, you have more energy. However, if you then suffer a stomach wound and the food therein seeps into the abdomen, you quickly die of sepsis. If, on the other hand, you eat only little, you are weakened but have a better chance of survival in case of a bullet in the abdomen.

A sound conclusion had never made it to the trenches. From the post-war medical history literature, it may be concluded that 40 - 50 % of the wounded did survive an operation, provided the person was in overall good health. With a weakened body and immune system however, as in the last years of the war, the chance of survival decreased.(2)

The early morning air was freezing cold and chilled the fearful bodies. If only you could smoke a cigarette now! The steel helmet sat ice-cold on the head and limited the quality of vision and hearing. The men were ready in full combat gear; each had his rifle or submachine gun at the ready. The demolition squad had their rifles around their necks so that they had their hands free for the sticks of dynamite and hand grenades.

Corporal Friedrich Albrecht was the Second in Command and would take over in case Clemens fell.

An artillery forward observer captain and his signallers set up shop in the trench of Clemens. They installed a field telephone and established contact with the rear artillery position. With his binoculars, the captain carefully inspected the enemy landscape.

"You follow my orders!" the artillery officer instructed the raiding infantrymen. "I'll tell you exactly when the assault starts. Only on my command do you go over of the top! As soon as you are out there, you follow the orders of your own commander."

Absolute trust was required.

The artillery captain gave the order by phone for his battery to commence firing according to the coordinates he had given them. Direct hits on the Russians were scored. The captain was still on the phone with his gunners as the last rounds were whistling through the air and simultaneously he shouted the order to Clemens and his men to get going.

They instantly jumped out of the trenches and rushed for their targets as fast as they could. Everyone knew what they had to do. They all knew their destination. For the first time they entered the area they had observed for so long from their trenches; the clearing with pale winter grass. The ground was uneven and they were also no longer used to fast sprinting. It was only the adrenaline that pushed the men across the field like nimble gazelles. Occasionally the ice in frozen puddles cracked sending the boot into the mud with a smacking sound. Quick, quick, keep on. Just don't stumble. Feet up.

The Russians remained under cover. Every soldier, whether Russian or German, knew that an attack was imminent when artillery fire kept them down. There was nothing else to do except crouching deep down waiting for the shelling to stop. But by then it was often too late!

(1) Forward observer on field telephone, Russia 1943.

Photographer: Göttert. Title: Russland, vorgeschobener Beobachter am Feldfernsprecher. Dezember 1943. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1985-022-25 / Göttert / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Wiki Commons.

(2) Behrendt, Karl Philipp: Die Kriegschirurgie von 1939-1945 aus der Sicht der beratenden Chirurgen des deutschen Heeres im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Dissertation. Institut für Geschichte der Medizin der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität. Freiburg/Br. 2003. S. 123 ff.

Excerpt from Chapter 7:

At the Front in Normandy

Context

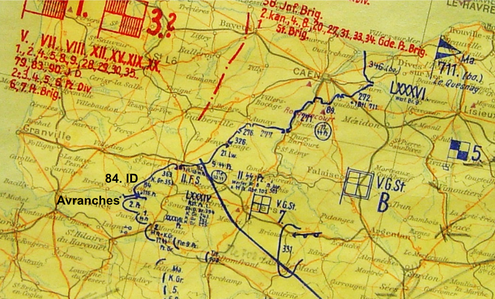

In February 1944, Clemens was transferred to France to the 84th Infantry Division.

After the Allies had broken through the German front at Avranches in Normandy in July 1944, the 84th Infantry Division was deployed at this breakthrough point.

General Staff map of 6th August 1944

5th August 1944

Clemens tried to mentally prepare himself for battle. But what would a fight against Americans be like? According to his experience from Russia, he imagined that the enemy here would similarly throw masses of infantry against the Germans. He felt reasonably prepared for such a situation. Then he spotted heavily armed soldiers sneaking through his area. They looked terrible; worn out, kaputt, broken, demoralized. Their distinctive helmets and long smocks identified them as paratroopers. They were elite soldiers who had a reputation for being particularly good fighters.

"What is going on?" Clemens asked a paratrooper, shocked at the sight. The man waved his hand in tired frustration.

"You sit in your hole, well camouflaged, and it's simply raining down bombs. Metre after metre of land all around you explode into the air. No cover will help. Survival is purely by chance." There was not much left of the elite unit even though no American or English infantryman had even set foot in their lines.

"If that was the elite of the German forces" thought Clemens, "how will we fare?!"

He realized that the war was now being waged from the air. The conditions were very different from those in Russia. His hopes of being able to master the approaching fighting situation as an infantryman were shaken.

(1) Paratroopers after the Allied invasion in Normandy in summer 1944. Photographer: Slickers. Title: Frankreich, Normandie, Fallschirmjäger auf Landstraße, Juni 1944, Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-586-2225-16/ Slickers / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Wikimedia Commons.

Table of Contents

- By Train from Cologne to the Front in Russia - 1942

- Summer Offensive - 1942

- In the Rshew Salient - 1942

- Military Training - 1943

- Return to the Eastern Front - 1943

- Waiting for the Allies to Land in France - 1944

- At the Front in Normandy - 1944

- In the Falaise Pocket - 1944

- Prisoner of War in the United States - 1944 - 45

- Return to Germany - 1946

- Fate of 95th and 84th Infantry Divisions - 1945

- Remains of the War

- Facts and Figures

- Organization of the 95th Infantry Division

- Equipment of a Front Infantryman

- Soldier and Author

- Bibliography

- Photo Credits

520 pages with over 300 photos, military maps and graphs

Excerpt of the Bibliography

1. Records of Military Units (Selection)

Reference Bundesarchiv - Militärarchiv Freiburg (Breisgau)

RW-4 Oberkommando der Wehrmacht / Wehrmachtführungsstab (OKW)

RH-2 Oberkommando des Heeres / Generalstab des Heeres (OKH)

April - September 1942 - Spring and Summer Offensive

RH 26-95 95. Infanterie-Division

RH-26-95 / 24 95. Infanterie-Division. Kriegstagebuch

Teil IV. In der Winterstellung ab April 1942

Teil V. Beginn der Sommeroffensive 1942

RH-26-95 / 25 Anlagenband zum Kriegstagebuch Nr. 3. April - Juni 42

RH 26-95 / 26 Anlagen zum Kriegstagebuch Nr. 3. Juli - 17. August 1942

RH-26-95 / 43 Tätigkeitsberichte der Abteilung Ic und IIa. April - Juli 1942

RH 20-2 2. Armee (AOK 2)

RH 20-2 / 395 Planspiel der 2. Armee Operation der Armeegruppe von Weichs am Nordflügel der Heeresgruppe Süd.

Mai - Juni 1942

Band 1: Allgemeines

Band 2: Befehle zum Planspiel

Band 3 und 4: 4. Panzer-Armee

Band 5: LV. AK 31.5.42. Zeitplan, Gliederung

Band 6: LV AK 15.6.42. Korpsbefehl für den Angriff

RH 20-2 / 451 K Lagekarten 28.6. - 18.7.42 (Sommeroffensive)

October - December 1942 - Rshew, Lutschessa-Valley

RH 19 VI Heeresgruppe Süd

RH 26-95 95. Infanterie-Division

RH 26-95/29 Kriegstagebuch der 95. Infanterie-Division

RH 26-95/44 95. ID: Tätigkeitsbericht der Abteilung Ic. 1. August bis 31. Dezember 1942

RH 26-95/50 95. ID: Tätigkeitsbericht der Abteilung IIa, 1. August - 31. Dezember 1942